Recent Times

From the 1500s onwards, the development of the modern market economy brought an intensification of farming, including the enclosure (fencing off) of both ‘common land’, and of previously unproductive ‘waste land’, both of which had been publicly-accessible open space until then. Common land was owned collectively by a number of persons or by one person, but over which other people had certain traditional rights allowing them to use it. Waste land was ground that was difficult to use because it was on a steep slope, had poor soil or was over-exposed to the weather. It is not known exactly how much common land there was in the Reserve, although there seems to have been a considerable amount, but it is clear that there was much waste land (some of which may have been ‘common’), especially the Glens and Fairlight Down.

This large-scale historic combination of common and waste land in what is now the Reserve gave local people the feeling that the whole area was 'theirs', and it was this deep belief that gave the driving-force to the creation of the Reserve in recent years.

The enclosing of Fairlight Down took place over a long period, with an early example being what are today the picnic area on Fairlight Road and its adjoining fields, between Martineau Lane and Mill Lane. A 1728 map of the Fairlight Place estate describes this area as 'Down enclosed'.

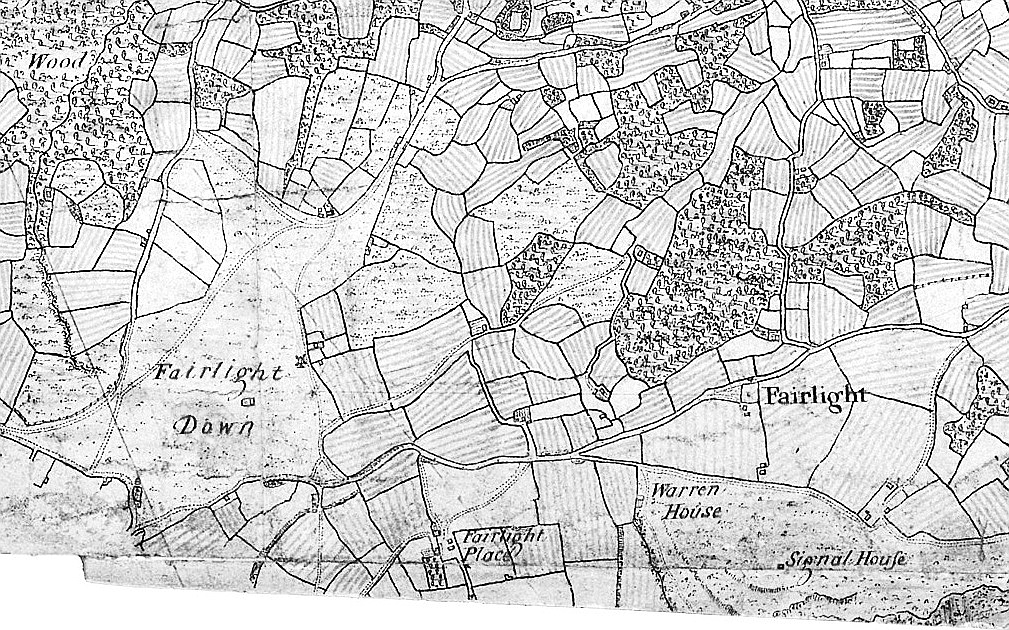

The earliest Ordnance Survey drawings, around 1800, show two main areas of waste land: (1) Fairlight Down, between today’s Martineau Lane in the east and Old London Road in the west, and from Fairlight Road in the south to Rye Road in the north; and (2) the Firehills and the east side of Warren Glen. Ironically, the ground which was most often said to be ‘common land’ in the 19th and 20th centuries - the East Hill - is shown in these and other early maps as being enclosed. It seems to have become (or returned to being) open ground soon after the Milward Estate passed into the hands of Sarah Milward in 1833.

This 1797 OS surveyor's drawing has unfortunately lost its bottom. There is a windmill in Mill Lane, opposite the farmhouse which is still there. The Signal House is on the site of today's Coastguard Station. A 1799 drawing, too poor to reproduce, shows similar features.

This 1797 OS surveyor's drawing has unfortunately lost its bottom. There is a windmill in Mill Lane, opposite the farmhouse which is still there. The Signal House is on the site of today's Coastguard Station. A 1799 drawing, too poor to reproduce, shows similar features.

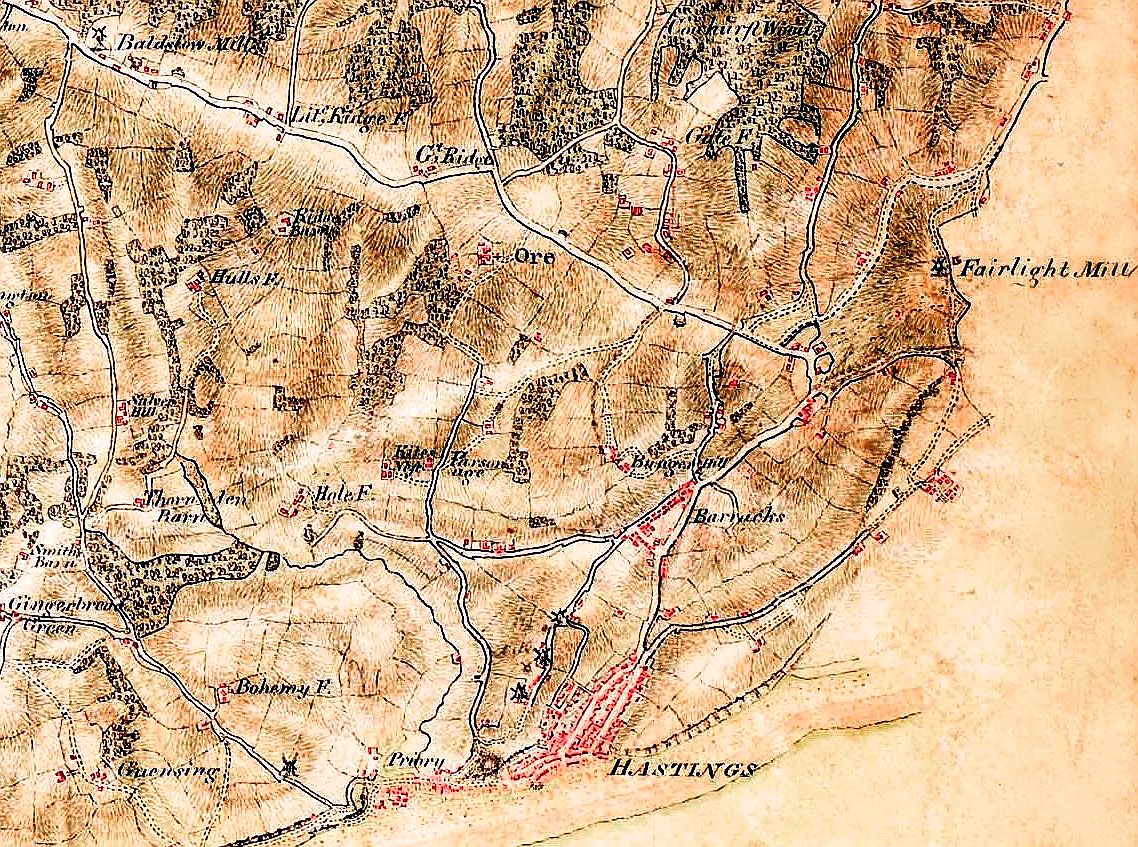

An 1806 drawing by another surveyor only went as far east as Mill Lane, and the windmill opposite the farm (not at what is now North's Seat. Hastings at that time was almost all in the Bourne Valley.

An 1806 drawing by another surveyor only went as far east as Mill Lane, and the windmill opposite the farm (not at what is now North's Seat. Hastings at that time was almost all in the Bourne Valley.

The best picture of the intensification of farming from the 1500s comes in the tithe maps of 1839. The prominent Milward family then farmed nearly all their land which is now in the Reserve from two farms. The larger of these was Fishponds Farm, in Barley Lane. The 1839 map shows this was let to Mr Isaac Arkcoll, who was then looking after 720 acres of Milward farmland south of Fairlight Road, from the west side of the East Hill to the estate boundary in Warren Glen. Some of the 720 acres was later sold off (including Shear Barn Farm), but in 1839 Mr Arkcoll had been responsible for all the farmland now in the Reserve, south of Fairlight Road and west of the Milward boundary in Warren Glen. The East Hill was all open pasture, while the rest of Fishponds Farm was mostly a mixture of pasture and arable. There were only about 40 acres of woodland, which was mainly coppiced, except for that in the gills.

The other Milward farm in 1839 was Tilekiln Lane Farm, run by Mr John Corner. The farmhouse was at the south end of Tilekiln Lane, while its barns were in Fairlight Road, between today’s Fairlight Avenue and Beacon Road. This farm looked after all the Milward farmland north of Fairlight Road in the Fairlight Down area, plus the 38 acres between Fairlight Road and Pinders Shaw, west of Tilekiln Lane (ie, the top of the Bourne Valley). The Milwards sold the farm in 1920. The Reserve land which was not then owned by the Milwards came under Mr William Lucas-Shadwell.

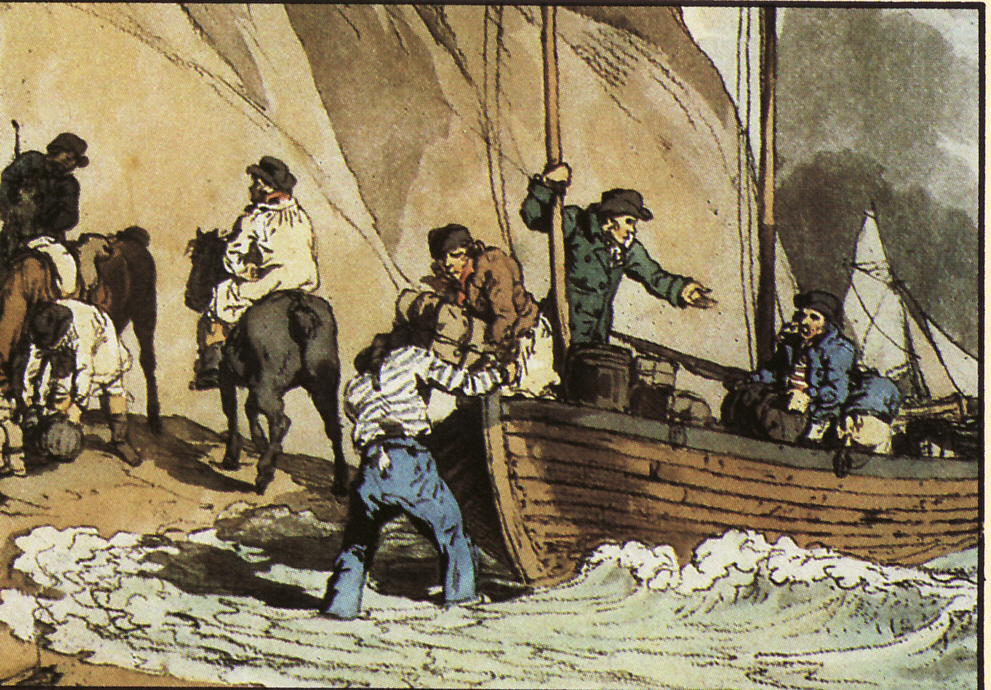

In the 18th and early 19th centuries the second most significant activity in the Reserve, after farming, was smuggling. The indented cliffs and glens created ideal obscure landing beaches, while the deep, dark glens provided concealed routes for transporting goods inland. Graham Smith says in Something to Declare: 'From the late 17th up until the early 19th century, smuggling was a major crime conducted on a colossal scale, the execution of which was violent, ruthless and bloody in the extreme, even when judged by the brutal standards of the time. The smugglers were encouraged and financed by the local gentry, protected by compliant magistrates, condoned by the clergy, aided and abetted by the ordinary people and at times facilitated by venal revenue officers. The illegal trade extended throughout the country and permeated every level of society; the smuggled goods found their way into virtually all households, from the most lowly to the highest.' It was widely believed that the 'venal revenue officers' included the local establishment figures John Collier and Edward Milward Snr, who, as senior Customs officers, acquired from smuggling a large part of the money with which they bought the smugglers well-used land that became the Reserve - land they were, in theory, policing. Without smuggling, the Reserve as we know it would not exist.

Smugglers unloading on the beach, with a Customs and Excise Revenue cutter closing in.

Smugglers unloading on the beach, with a Customs and Excise Revenue cutter closing in.

From 1815 smuggling became a particulary serious problem because it was taken up by many former soldiers and sailors who became unemployed when the Napoleonic war ended. Not only did the government lose large amounts of revenue from import duties, but the smugglers began using their military experience to become well-organised, armed and often violent insurgents who were challenging the state’s ability to maintain order. To bring the situation under control, the Navy-run Coast Blockade Service (the forerunner of today’s Coastguard) built ‘watch houses’ round the south east coast, where armed sailors lived and opposed the smugglers. In 1819 the Coast Blockade constructed one on a small plateau near the bottom of the cliff, just east of Ecclesbourne Stream. Others were also built on Fairlight Head and the Haddocks in Fairlight Cove. The Ecclesbourne Station was washed away in 1859 and replaced in 1864 by another on top of the cliff, west of the stream, which went over the cliff in 1963. Some parts of it are still visible. The Fairlight Station was rebuilt in 1904.

Warren Glen and Warren Cottage in 1851. The Coastguard Station is on the hill behind.

Warren Glen and Warren Cottage in 1851. The Coastguard Station is on the hill behind.

Smuggling rapidly declined in the 1830s, nationally and locally, while the Reserve was becoming increasingly important as a major attraction for visitors to Hastings. The cliffs and glens had been popular since the late 18th century, but it was the relaxed attitude of the Milwards as land owners, especially Sarah Milward of Fairlight Place following her inheritance of the Milward Estate in 1833, that allowed and encouraged large numbers of people of all classes to freely use the area for many different non-work pursuits. The Lucas-Shadwells of Fairlight Hall in Martineau Lane may have shared that approach. The completion of the local railway lines in 1851 soon established Hastings as a popular resort for not-so-well-off south Londoners seeking a few hours or days amusement in pubs, on beaches and along the cliff-tops. This came to a climax in the 1950s, when on the cliffs and in the glens there were cafes, campers, golf-players, football and cricket pitches, kiddies playing on their own, fruit pickers, swimmers and people just ‘walking the glens’ (with not so many dogs as today).

Nine-tenths of the land now comprising the Reserve was mostly sold to Hastings Council by the Milward family. They, and the related Collier family, had acquired three-quarters of that land (everything as far east as the east side of Warren Glen) in the 18th and early 19th centuries, and the remainder (the rest of the glen and part of the Firehills) probably in 1917.

In the 19th century, the Milwards’ neighbour to the east (and the only other owner of a significant amount of the Reserve) was the Lucas-Shadwell family. They, like the Milwards, came from respectable Sussex backgrounds, and used their establishment contacts and professional skills to acquire large quantities of land, most of it between Fairlight and the River Rother south of Rye. The Milwards and Lucas-Shadwells were acquisitive and hard in many ways, but were generous in the help they gave to local causes. They were also not only neighbours in the countryside but also in Hastings: the Milwards’ town-house was Old Hastings House, at the top of the High Street, while the Lucas-Shadwells lived directly opposite across the Bourne Stream, in what became the All Saints Rectory at the top of All Saints Street. Both buildings are still there.

The first area to be acquired from the Milward/Collier descendants by the Council was the 60 acres of the East Hill, which was bought for a high price in 1888, along with 24 acres of the West Hill. This was widely criticised at the time because, as the Hastings News said, the Council was simply paying for 'that which has been practically the right of the inhabitants for centuries: the free use of these hills as a place of healthy recreation' - a form of common land. The family sold 215 acres of the clifftop walks and much of the glens to the Council in 1951, in an exchange deal. The 394 acres of Fairlight Place Farm and 51 acres of adjoining Church Farm were purchased from the Milwards in 1963. In addition, five acres of the Spoon reservoir was bought in 1924 and North’s Seat in 1938. In 1959 about 21 acres of clifftop was given to the Council following a landslip. The largest area of today’s Reserve land not obtained from the Milward/Colliers is the Firehills; 69 acres were bought from a local resident in 1927.